Brackets: ( ) page numbers for Dover Edition (Crew and de Salvio) ; [ ] paging in National Edition

Two New Sciences, pp. 153-160

THIRD DAY

[190]

CHANGE OF POSITION [De Motu Locali]

My purpose is to set forth a very new science dealing with a very ancient subject. There is, in nature, perhaps nothing older than motion, concerning which the books written by philosophers are neither few nor small; nevertheless I have discovered by experiment some properties of it which are worth knowing and which have not hitherto been either observed or demonstrated. Some superficial observations have been made, as, for instance, that the free motion [naturalem motum] of a heavy falling body is continuously accelerated;* but to just what extent this acceleration occurs has not yet been announced; for so far as I know, no one has yet pointed out that the distances traversed, during equal intervals of time, by a body falling from rest, stand to one another in the same ratio as the odd numbers beginning with unity. **

It has been observed that missiles and projectiles describe a curved path of some sort; however no one has pointed out the fact that this path is a parabola. But this and other facts, not few in number or less worth knowing, I have succeeded in proving; and what I consider more important, there have been opened up to this vast and most excellent science, of which my (154) work is merely the beginning, ways and means by which other minds more acute than mine will explore its remote corners.

This discussion is divided into three parts; the first part deals with motion which is steady or uniform; the second treats of motion as we find it accelerated in nature; the third deals with the so-called violent motions and with projectiles. [191]

UNIFORM MOTION

In dealing with steady or uniform motion, we need a single definition which I give as follows:

DEFINITION

By steady or uniform motion, I mean one in which the distances traversed by the moving particle during any equal intervals of time, are themselves equal.

CAUTION

We must add to the old definition (which defined steady motion simply as one in which equal distances are traversed in equal times) the word "any," meaning by this, all equal intervals of time; for it may happen that the moving body will traverse equal distances during some equal intervals of time and yet the distances traversed during some small portion of these time-intervals may not be equal, even though the time intervals be equal.

From the above definition, four axioms follow, namely:

AXIOM I

In the case of one and the same uniform motion, the distance traversed during a longer interval of time is greater than the distance traversed during a shorter interval of time.

AXIOM II

In the case of one and the same uniform motion, the time required to traverse a greater distance is longer than the time required for a less distance. (155)

AXIOM III

In one and the same interval of time, the distance traversed at a greater speed is larger than the distance traversed at a less speed. [192]

AXIOM IV

The speed required to traverse a longer distance is greater than that required to traverse a shorter distance during the same time-interval.

THEOREM I, PROPOSITION I

If a moving particle, carried uniformly at a constant speed, traverses two distances the time-intervals required are to each other in the ratio of these distances.

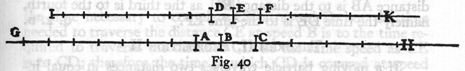

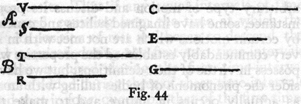

Let a particle move uniformly with constant speed through two distances AB, BC, and let the time required to traverse AB be represented by DE; the time required to traverse BC, by EF; then I say that the distance AB is to the distance BC as the time DE is to the time EF.

Let the distances and times be extended on both sides towards G, H and I, K; let AG be divided into any number whatever of spaces each equal to AB, and in like manner lay off in DI exactly the same number of time-intervals each equal to DE. Again lay off in CH any number whatever of distances each equal to BC; and in FK exactly the same number of time-intervals each equal to EF; then will the distance BG and the time EI be equal and arbitrary multiples of the distance BA and the time ED; and likewise the distance HB and the time KE are equal and arbitrary multiples of the distance CB and the time FE.

And since DE is the time required to traverse AB, the whole (156) time EI will be required for the whole distance BG, and when the motion is uniform there will be in EI as many time-intervals each equal to DE as there are distances in BG each equal to BA; and likewise it follows that KE represents the time required to traverse HB.

Since, however, the motion is uniform, it follows that if the distance GB is equal to the distance BH, then must also the time IE be equal to the time EK; and if GB is greater than BH, then also IE will be greater than EK; and if less, less. * There [193] are then four quantities, the first AB, the second BC, the third DE, and the fourth EF; the time IE and the distance GB are arbitrary multiples of the first and the third, namely of the distance AB and the time DE.

But it has been proved that both of these latter quantities are either equal to, greater than, or less than the time EK and the space BH, which are arbitrary multiples of the second and the fourth. Therefore the first is to the second, namely the distance AB is to the distance BC, as the third is to the fourth, namely the time DE is to the time EF. Q.E.D.

THEOREM II, PROPOSITION II

If a moving particle traverses two distances in equal intervals of time, these distances will bear to each other the same ratio as the speeds. And conversely if the distances are as the speeds then the times are equal.

Referring to Fig. 40, let AB and BC represent the two distances traversed in equal time-intervals, the distance AB for instance with the velocity DE, and the distance BC with the velocity EF. Then, I say, the distance AB is to the distance BC as the velocity DE is to the velocity EF. For if equal multiples of both distances and speeds be taken, as above, namely, GB and IE of AB and DE respectively, and in like manner HB and KE of BC and EF, then one may infer, in the same manner as above, that the multiples GB and IE are either less than, equal (157) to, or greater than equal multiples of BH and EK. Hence the theorem is established.

THEOREM III, PROPOSITION III

In the case of unequal speeds, the time-intervals required to traverse a given space are to each other inversely as the speeds.

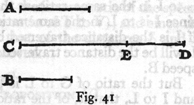

Let the larger of the two unequal speeds be indicated by A; the smaller, by B; and let the motion corresponding to both traverse the given space CD. Then I say the time required to traverse the distance CD at speed A is to the time required to traverse the same distance at speed B, as the speed B is to the speed A. For let CD be to CE as A is to B; then, from the preceding, it follows that the time required to complete the distance CD at speed A is the same as

[194]

the time necessary to complete CE at speed B; but the time needed to traverse the distance CE at speed B is to the time required to traverse the distance CD at the same speed as CE is to CD; therefore the time in which CD is covered at speed A is to the time in which CD is covered at speed B as CE is to CD, that is, as speed B is to speed A. Q.E.D.

[194]

the time necessary to complete CE at speed B; but the time needed to traverse the distance CE at speed B is to the time required to traverse the distance CD at the same speed as CE is to CD; therefore the time in which CD is covered at speed A is to the time in which CD is covered at speed B as CE is to CD, that is, as speed B is to speed A. Q.E.D.

THEOREM IV, PROPOSITION IV

If two particles are carried with uniform motion, but each with a different speed, the distances covered by them during unequal intervals of time bear to each other the compound ratio of the speeds and time intervals.

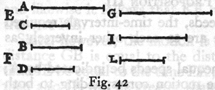

Let the two particles which are carried with uniform motion be E and F and let the ratio of the speed of the body E be to that of the body F as A is to B; but let the ratio of the time consumed by the motion of E be to the time consumed by the motion of F as C is to D. Then, I say, that the distance covered by E, with speed A in time C, bears to the space traversed by F with speed (158) B in time D a ratio which is the product of the ratio of the speed A to the speed B by the ratio of the time C to the time D. For if G is the distance traversed by E at speed A during the time-interval C, and if G is to I as the speed A is to the speed B; and if also the time-interval C is to the time-interval D as I is to L, then it follows that I is the distance traversed by F in the same time that G is traversed by E since G is to I in the same ratio as the speed A to the speed B. And since I is to L in the same ratio as the time-intervals C and D, if I is the distance traversed by F during the interval C, then L will be the distance traversed by F during the interval D at the speed B.

But the ratio of G to L is the product of the ratios G to I and I to L, that is, of the ratios of the speed A to the speed B and of the time-interval C to the time-interval D. Q.E.D.

[195]THEOREM V, PROPOSITION V

If two particles are moved at a uniform rate, but with unequal speeds, through unequal distances, then the ratio of the time-intervals occupied will be the product of the ratio of the distances by the inverse ratio of the speeds.

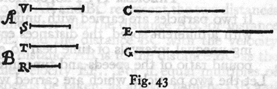

Let the two moving particles be denoted by A and B, and let the speed of A be to the speed of B in the ratio of V to T; in like manner let the distances traversed be in the ratio of S to R; then I say that the ratio of the time-interval during which the motion of A occurs to the time-interval occupied by the motion of B is the product of the ratio of the speed T to the speed V by the ratio of the distance S to the distance R.

Let C be the time-interval occupied by the motion of A, and (159) let the time-interval C bear to a time-interval E the same ratio as the speed T to the speed V.

And since C is the time-interval during which A, with speed V, traverses the distance S and since T, the speed of B, is to the speed V, as the time-interval C is to the time-interval E, then E will be the time required by the particle B to traverse the distance S. If now we let the time-interval E be to the time interval G as the distance S is to the distance R, then it follows that G is the time required by B to traverse the space R. Since the ratio of C to G is the product of the ratios C to E and E to G (while also the ratio of C to E is the inverse ratio of the speeds of A and B respectively, i.e., the ratio of T to V); and since the ratio of E to G is the same as that of the distances S and R respectively, the proposition is proved. [196]

THEOREM VI, PROPOSITION VI

If two particles are carried at a uniform rate, the ratio of their speeds will be the product of the ratio of the distances traversed by the inverse ratio of the time-intervals occupied.

Let A and B be the two particles which move at a uniform rate; and let the respective distances traversed by them have the ratio of V to T, but let the time-intervals be as S to R. Then I say the speed of A will bear to the speed of B a ratio which is the product of the ratio of the distance V to the distance T and the time-interval R to the time-interval S.

Let C be the speed at which A traverses the distance V during the time-interval S; and let the speed C bear the same ratio to another speed E as V bears to T; then E will be the speed at which B traverses the distance T during the time-interval S. If now the speed E is to another speed G as the time-interval R is to the time-interval S, then G will be the speed at which the (160) particle B traverses the distance T during the time-interval R. Thus we have the speed C at which the particle A covers the distance V during the time S and also the speed G at which the particle B traverses the distance T during the time R. The ratio of C to G is the product of the ratio C to E and E to G; the ratio of C to E is by definition the same as the ratio of the distance V to distance T; and the ratio of E to G is the same as the ratio of R to S. Hence follows the proposition.

SALV. The preceding is what our Author has written concerning uniform motion. We pass now to a new and more discriminating consideration of naturally accelerated motion, such as that generally experienced by heavy falling bodies; following is the title and introduction.