24. Moments of Inertia and Rolling Motion

Michael Fowler

Examples of Moments of Inertia

Molecules

The moment of inertia of the hydrogen molecule was historically important. It’s trivial to find: the nuclei (protons) have 99.95% of the mass, so a classical picture of two point masses a fixed distance apart gives In the nineteenth century, the mystery was that equipartition of energy, which gave an excellent account of the specific heats of almost all gases, didn’t work for hydrogenat low temperatures, apparently these diatomic molecules didn’t spin around, even though they constantly collided with each other. The resolution was that the moment of inertia was so low that a lot of energy was needed to excite the first quantized angular momentum state, . This was not the case for heavier diatomic gases, since the energy of the lowest angular momentum state is lower for molecules with bigger moments of inertia .

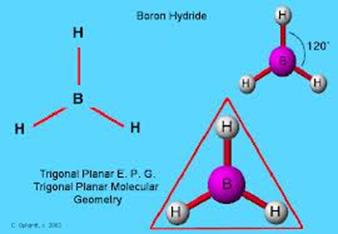

Here’s a simple planar molecule:

Obviously, one principal axis is through the centroid, perpendicular to the plane. We’ve also established that any axis of symmetry is a principal axis, so there are evidently three principal axes in the plane, one along each bond! The only interpretation is that there is a degeneracy: there are two equal-value principal axes in the plane, and any two perpendicular axes will be fine. The moment of inertial about either of these axes will be one-half that about the perpendicular-to-the-plane axis.

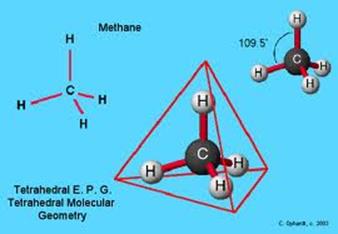

What about a symmetrical three dimensional molecule?

Here we have four obvious principal axes: only possible if we have spherical degeneracy, meaning all three principal axes have the same moment of inertia.

Various Shapes

A thin rod, linear mass density length :

A square of mass , side , about an axis in its plane, through the center, perpendicular to a side: (It’s just a row of rods.) in fact, the moment is the same about any line in the plane through the center, from the symmetry, and the moment about a line perpendicular to the plane through the center is twice thisthat formula will then give the moment of inertia of a cube, about any axis through its center.

A disc of mass radius and surface density has This is also correct for a cylinder (think of it as a stack of discs) about its axis.

A disc about a line through its center in its plane must be from the perpendicular axis theorem. A solid cylinder about a line through its center perpendicular to its main axis can be regarded as a stack of discs, of radius , height , taking the mass of a disc as , and using the parallel axes theorem,

For a sphere, a stack of discs of varying radii,

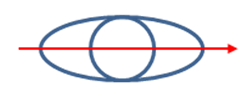

An ellipsoid of revolution and a sphere of the same mass and radius clearly have the same motion of inertial about their common axis (shown).

Moments of Inertia of a Cone

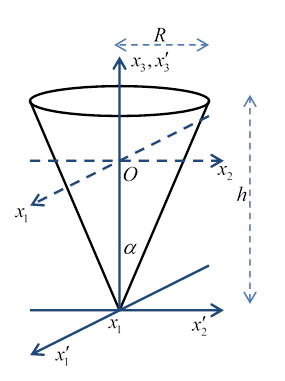

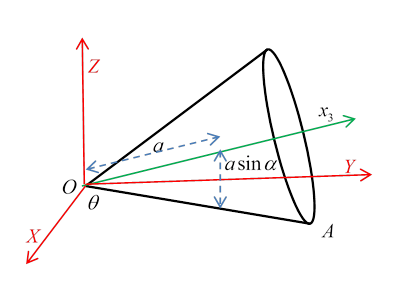

Following Landau, we take height and base radius and semivertical angle so that .

As a preliminary, the volume of the cone is

The center of mass is distance from the vertex, where

The moment of inertia about the central axis of the cone is (taking density ) that of a stack of discs each having mass and moment of inertia :

The moment of inertia about the axis through the vertex, perpendicular to the central axis, can be calculated using the stack-of-discs parallel axis approach, the discs having mass , it is

Analyzing Rolling Motion

Kinetic Energy of a Cone Rolling on a Plane

(This is from Landau.)

The cone rolls without slipping on the horizontal plane. The momentary line of contact with the plane is , at an angle in the horizontal plane from the axis.

The important point is that this line of contact, regarded as part of the rolling cone, is momentarily at rest when it’s in contact with the plane. This means that, at that moment, the cone is rotating about the stationary line Therefore, the angular velocity vector points along

Taking the cone to have semi-vertical angle (meaning this is the angle between and the central axis of the cone) the center of mass, which is a distance from the vertex, and on the central line, moves along a circle at height above the plane, this circle being centered on the axis, and having radius . The center of mass moves at velocity , so contributes translational kinetic energy Now visualize the rolling cone turning around the momentarily fixed line : the center of mass, at height , moves at , so the angular velocity

Next, we first define a new set of axes with origin : one, , is the cone’s own center line, another, , is perpendicular to that and to , this determines . (For these last two, since they’re through the vertex, the moment of inertia is the one worked out at the end of the previous section, see above.)

Since is along , its components with respect to these axes are .

However, to compute the total kinetic energy, for the rotational contribution we need to use a parallel set of axes through the center of mass. This just means subtracting from the vertex perpendicular moments of inertia found above a factor

The total kinetic energy is

using

Rolling Without Slipping: Two Views

Think of a hoop, mass radius , rolling along a flat plane at speed . It has translational kinetic energy angular velocity and moment of inertia so its angular kinetic energy , and its total kinetic energy is .

But we could also have thought of it as rotating about the point of contactremember, that point of the hoop is momentarily at rest. The angular velocity would again be , but now with moment of inertia, from the parallel axes theorem, , giving same total kinetic energy, but now all rotational .

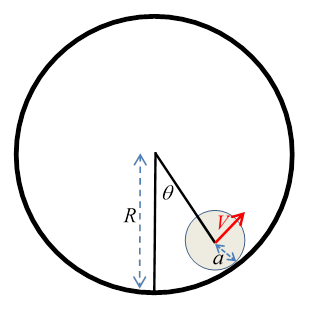

Cylinder Rolling Inside another Cylinder

Now consider a solid cylinder radius rolling inside a hollow cylinder radius , angular distance from the lowest point , the solid cylinder axis moving at , and therefore having angular velocity (compute about the point of contact)

The kinetic energy is

The potential energy is

The Lagrangian , the equation of motion is

so small oscillations are at frequency .