In the previous lecture, we focused on the functions from the complex potential its real part the potential from a single line of charge, its imaginary part the potential between conducting plates at different potentials meeting along a line.

In this lecture, we’ll investigate the potentials from the complex expression for two parallel lines of charge. Remarkably, this provides straightforward solutions to some tough Jackson problems: 2.8, 2.13, 2.14, possibly others. And, in this approach the equipotentials are apparent from the start, whereas the infinite series solutions give almost no insight without a lot of further work.

We take two infinite line charges, linear charge density in the -direction, located at

Omitting the overall factor to reduce clutter, the potential is the real part of the function

That is, the potential is:

The equipotentials are therefore given by

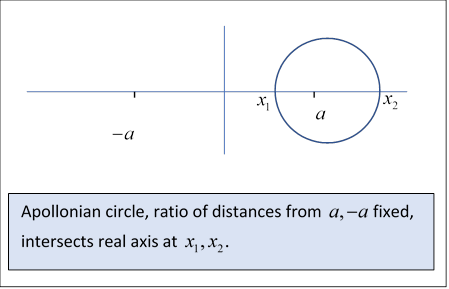

That is to say, the points in the plane at potential are those whose distances from the points are in the same ratio But we met this condition previously, in finding the image point for a charge outside a grounded sphere: these are the circles of Apollonius. (First found by the Greeks using geometric arguments, but you can easily verify the result with coordinates, and you can show the center is on the line through the two points, as it must of course be from symmetry.)

Our first task is to find the center and the radius of the circle corresponding to potential

Applying the above distance ratio formula to the points where the circle cuts the real axis,

Adding:

Multiplying by and subtracting,

Subtracting,

where is the radius of the circle, and adding,

where is the distance of the circle center from the origin, so

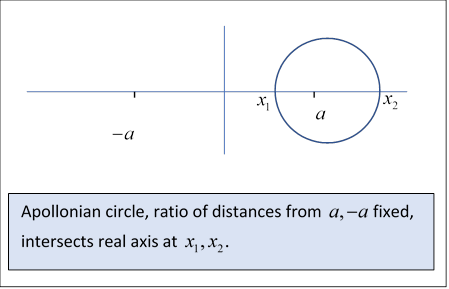

We’re now ready to consider the capacitance of two parallel circular cylinders using this result.

Recall

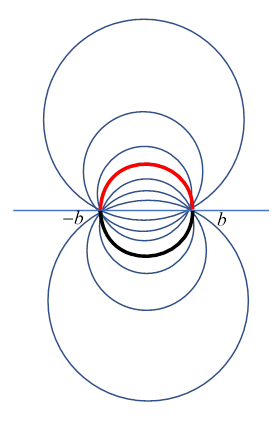

Evidently, from the diagram, the -axis, equidistant from both lines of charge, is the curve for and from the symmetry of the diagram, and correspond to circles of the same radius the same distance from the -axis in opposite directions.

We’ll take equipotentials at on opposite sides of the -axis, having (from the end of the previous section) radii and centers separated by

The potential difference (which is what we need to evaluate the capacitance) is of course but to evaluate this in terms of the radii and separation, which are all given in terms of hyperbolic functions of obviously we must first find then invert it to get the answer.

Now

We have cylinder center separation squared (and using )

In going to the last line, remember that have opposite signs, so

and the capacitance is (finally restoring the we removed at the beginning)

since we took unit linear charge density.

If one cylinder is inside the other, the same analysis carries through, except that the argument of the gains a minus sign.

Exercise: Check that for two parallel wires, radii distance apart,

Note: In the literature, for two cables of diameter with centers apart, the capacitance is given as This is equivalent to our result: put

switching to the more common notation, so

Hence

We’ve just found the potential from two parallel infinite line charges, in the -direction, located at to be the real part of the function

But we know that the imaginary part also satisfies Laplace’s equation: except at the two singular points. What system of charges could that represent?

Writing

Evidently the potential is

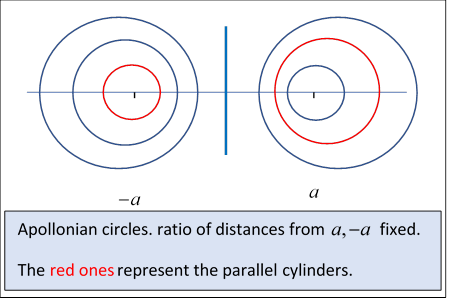

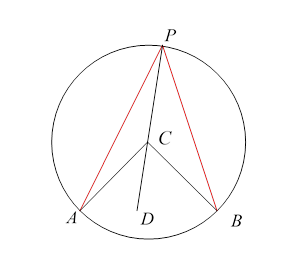

and equipotentials will be sets of points P such that lines from P to the two points will have angle between them. Actually these points are simple to find: you just need to recall some high school geometry.

Given a chord of a circle, the angle for any point on the circle above the chord is twice the angle where is the center of the circle. This follows from triangles being isosceles, so the exterior angle (which is the sum of the two other interior angles)is twice the angle Hence angle is half of the fixed angle independent of where is on the upper part of the circle.

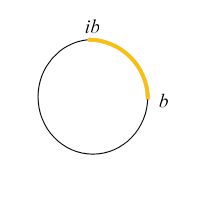

Hence the equipotentials are all the circles through the two points, except that if the arc above the two points is at potential the arc of the same circle below the two points is at potential (Note: not ) We’ve highlighted this for the circle having the two points as ends of a diameter.

This is Jackson problem 2.13, perfect for our equipotentials.

A circular conducting pipe is actually two half pipes held together with a thin layer of insulator at the ends of a horizontal diameter, at

We’ve switched from to to coincide with Jackson’s notation.

The top half is held at potential the bottom half at Find the potential inside. We’ll put in those potential values at the end, for now we’ll take

Recall so

To put this slightly differently, if we write

then

So the potential is the arctan of the ratio of the imaginary part to the real part of

A trick for finding this easily is to multiply both numerator and denominator by the complex conjugate of the denominator: this gives a real denominator, so it plays no role in determining the ratio of real to imaginary parts, and the numerator becomes

Writing in this expression, and separating out its real and imaginary parts, we immediately find

Looking at small values of we note that this potential is negative in the upper half plane, so to link up with Jackson’s problem 2.13 (and his angle ) we must switch the sign.

A final adjustment: Our result is equal to on the top half of the cylinder (see figure), on the bottom half. But we want something equal to on the top, on the bottom. It's easy to verify the correct expression is

Exercise: What about the potential outside the pipe? Sketch some field lines, inside and outside, to guide your thinking.

Again we'll look at a cut circular pipe, but this time just separate off one-quarter of the circle.

Suppose the quadrant (in the complex plane representation) between positive real and pure imaginary is at one potential, the other three-quarters of the circle at a different potential.

The obvious strategy is to think of angles based on the chord joining the two ends and so look at

The angle in a quadrant is (half the angle the chord subtends at the center of the circle).

This is by way of introduction to Jackson problem 2.14(b), in which all four quadrants are electrically insulated where they join, and alternate ones are at potentials We can achieve this by simply adding the opposite chord to the one above, giving the relevant function to be

As in the example above, the strategy is to multiply top and bottom by the complex conjugate of the denominator, then take arctan of the ratio of imaginary and real parts of the consequent numerator.

That is, the numerator becomes

and Jackson’s result follows (as before, we need to switch the sign.)

Exercise: try plotting the field lines just from a few facts: what do they look like near the joins? In the center? What about along the axes? The lines ?

After you've sketched it, compare with this.

The two sets of circles discussed above are the basis for an orthogonal coordinate system labeled bipolar (yes, really). Here is a very nice plot from Wikipedia and the link

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bipolar_coordinates#/media/File:Iso1.svg

In the Wikipedia article, the parameter is our and

They write

Exercise: Show this is equivalent to (from the beginning of this lecture)

Making a 3D rotation of this diagram about the -axis generates the 3D toroidal coordinate system.